The very first fighting games, from Cinematronics’ Warrior to Data East’s Karate Champ, all featured two identical characters facing each other in one-on-one combat. The now iconic Street Fighter began with two functionally identical yet visually and personably distinct playable characters, Ryu and Ken. It’s no surprise, then, that so-called clone characters have remained one of fighting games’ longest-standing traditions.

Just as pervasive as the clone is the act of “decloning”, or taking an existing clone and making them more unique in later releases. Many debate over whether Ken can still be called a true clone, and, if not, when he crossed the increasingly blurred line. This concept of where the clone becomes a character in its own right is perhaps best explored in Smash, where decloning has gone back and forth between an important goal of the development team and a betrayal of perceived fan desires.

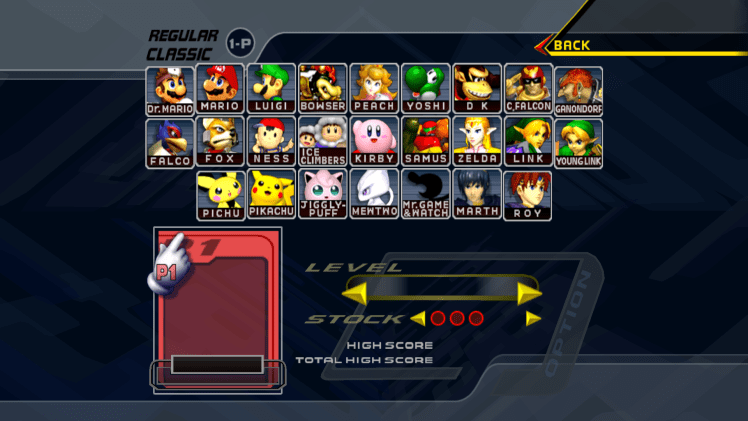

The original Super Smash Bros. features a starting roster of eight characters alongside four secret, unlockable characters which reuse assets. The degree to which each of these characters were really recycled varies greatly. Both Luigi and Ness utilized Mario as a base, but Luigi’s only unique attacks were his dash attack and down tilt. Ness may as well be original, copying only Mario’s getup attacks and polygonal model. Melee has similar highlights for its six clones. Officially called モデル替えキャラ or “model swap characters” at the time, these characters are recessed on the character select screen and appear directly next to their source character.

Brawl took the major step of cutting most clone characters and revamping the ones that returned, making it the first and, as of yet, only game in the series without a single true clone. Despite this, newcomers Lucas and Wolf took clear inspiration from Ness and Fox, and the term “pseudoclone” eventually came to be to describe such characters. Smash 4 immediately reverted this philosophy with two new clones, originally developed as alternate costumes and only turned into separate characters late in development. The level of overlap was embraced to the point of being lumped into other characters’ reveal trailers. Smash 4 also saw the return of fan favorite clones Dr. Mario and Roy, and the introduction of Mii Fighters, who largely copy their movesets from existing characters to allow for customization.

Ultimate finally saw an update to the official name for clone characters, now called Echo Fighters in the west and Dash Fighters in Japan. The label sought to make official a concept that had existed in the series from its very foundation, but instead acted only to further blur the definition; Ken controversially earned the title, unlike Dr. Mario, Pichu, and Young Link, whose differences from their source material largely amount to attribute changes. One can speculate that the Melee trio was awarded unique status due to its history with the series – every Echo Fighter originated either in Smash 4 or Ultimate – or that Ken is the special one due to his historical significance as the original clone.

Ultimate also brought with it a new concept in the recloning balance patch; while Daisy was already a clone of Peach, she at least had one notable attribute difference in her down special’s knockback values, but this difference was patched out in Ver. 3.0.0. This makes Daisy the closest character to an identical copy in series history, having just slightly different hitboxes in her idle and running animations… aside from Alph and the Koopalings, who don’t even get their own character slots, instead relegated to costumes. What makes a clone, then, has shifted drastically across the history of the series and even within individual games.

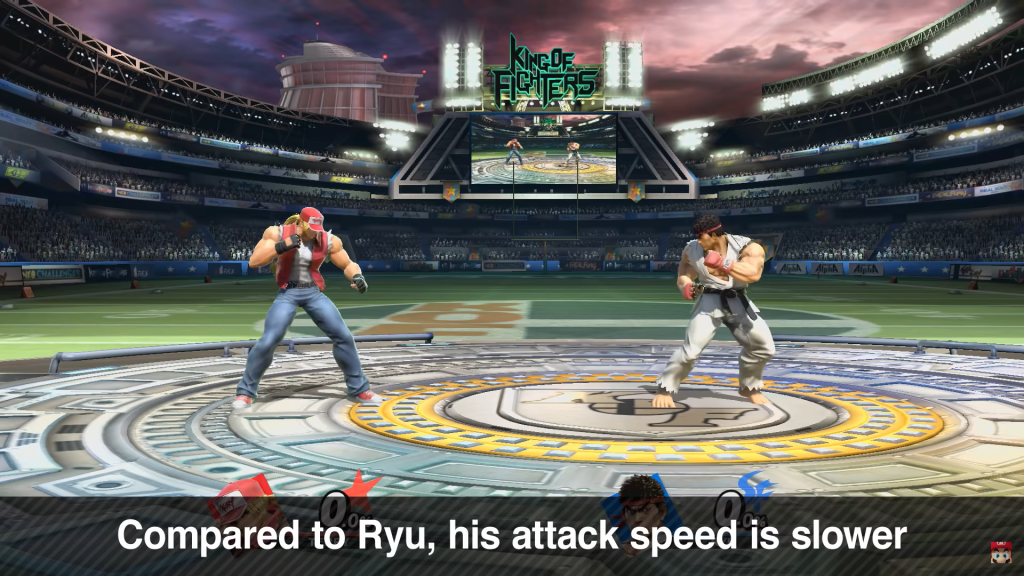

Another ambiguity exists in Ultimate‘s Terry. Despite having had his similarities with Ryu explicitly highlighted in his gameplay reveal presentation, his similarities end in what little was discussed. Many consider Terry not to be any sort of clone, alongside such borderline characters as Melee‘s Jigglypuff and Smash 64‘s Captain Falcon. We seem to have some ambiguous characters emerging, neither clone, semiclone, pseudoclone, nor non-clone.

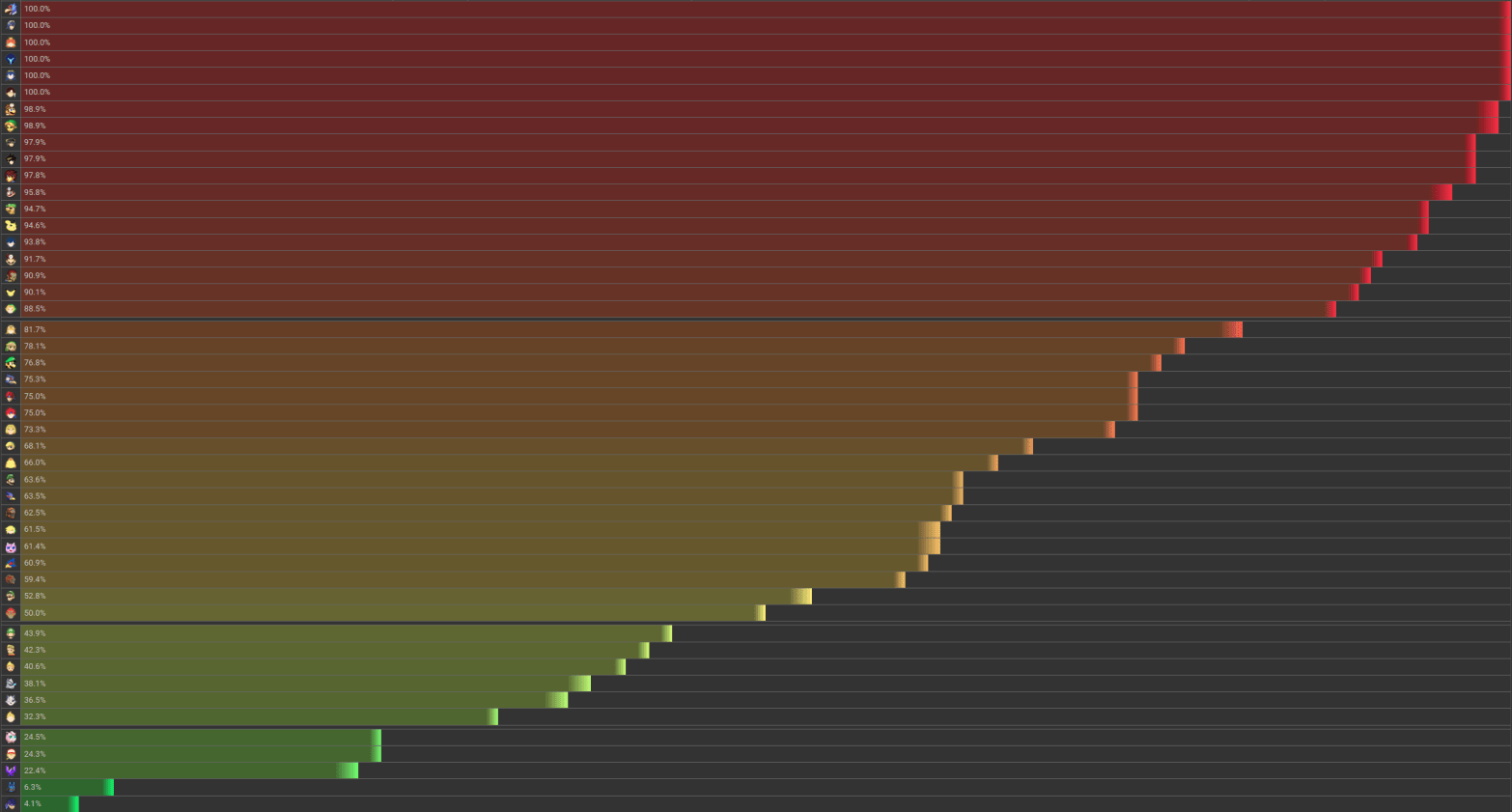

This article is inspired in part by Toomai’s “Cloneosity”, a work written for the sake of organizing clone characters on SmashWiki. To oversimplify, it involves a system of points awarded to characters for shared moves to reach a percentage score of similarity. This method is likely the most objective possible for creating a sort of “clone gradient”, and I always find myself coming back to it when considering this topic.

Where it loses this objectivity, though, is in its conclusion. Toomai’s categories are usually made by dividing at major gaps between groups of characters, but the largest gap by far (6.3%-22.4%) was ignored. The sixth largest, meanwhile, was chosen as a major dividing line to fit the term “semiclone” in implied meaning of “at least half”. Toomai acknowledges this, highlighting that Smash 4‘s Luigi (52.8%) and Ultimate‘s Ganondorf (50.0%) are “the most on-the-fence between any two categories”.

These decisions are, of course, human. As tempting as it may be to try to find perfect numbers that line up with how everyone thinks, the reality is that the concepts of “clones” and “semiclones” and “pseudoclones” are not naturally occuring. We’re not categorizing minerals, we’re reverse engineering the thought process of a team of developers who themselves have been trying to neatly explain decades of design and iteration.

Other games have toyed with ways to approach clone characters. Rushdown Revolt, an indie platform fighter, marketed Seth as a fusion character, described in his reveal trailer as “a fusion of Ashani and Weishan”, two other characters in the game. This created a completely different playstyle, and successfully avoids feeling like a clone while still efficiently using limited indie developer resources.

Tekken‘s core story revolves around clones, with the members of the Mishima family inheriting the Wind God Fist while still retaining their own identity. That story connection allows the act of decloning to then become a storytelling device. As Jin begins to rebel from his father, he develops a more traditional karate moveset, only to regress with the introduction of his Devil Jin form.

Street Fighter explores how Akuma’s temptation to learn the dark arts created the unique aspects of his moveset that separate him from Ryu. Even something as simple as Pichu hurting himself when he attacks creates the impression of an inexperienced fighter, while Pikachu demonstrates better control. Developers create clones not just to save resources, but to tell their stories and develop their worlds, and so the correct “level” of cloning has to balance all of these factors.

In early versions of “Cloneosity”, certain characters who hovered close to dividing lines were included in limbo zones. Toomai put it best in the intro to his analysis: “it’s a continuous scale, even if the terms are used in a fairly hardline fashion.” The only true clone, then, is along the lines of Street Fighter I‘s Ken or Smash Ultimate‘s Alph, differing in aesthetic alone. Any other character, from Daisy to Terry, exists elsewhere on the spectrum.

Most impressive are such characters as Melee‘s Falco, who are complete, 100% clones of their source material and yet offer a totally different way to play through numerical tweaks alone. Few Melee players would refer to Falco as anything short of his own character; small changes to his laser fundamentally change the neutral game, and stat adjustments for many of his other moves give him an entirely different set of combos. Despite this, his moveset is identical to the casual eye, and it’s difficult not to define him as a true clone.

Conversely, characters like Ganondorf have changed in the minds of players at different times than any moveset data would suggest. Ganondorf was introduced in Melee as a near-total clone of Captain Falcon, before being significantly decloned in Brawl. You wouldn’t know that if you asked the average player, though, who thinks he was decloned in Ultimate. There, he received a sword that appears twice in his entire toolkit, and is otherwise unchanged. That visual distinction entered the minds of most players far more successfully than any of the more significant changes he had received prior.

Returning to the title, then: what makes a clone has two potential answers. The literal answer is that what makes a clone is whatever they share in common with another character. Perhaps more thoughtfully, the clone is whatever differences manage to shine through in spite of the similarities, whatever new way to play emerges from within this box. Regardless of what we call each individual character, it doesn’t change how you can best develop your play with them, nor does it offer any meaningful insight into their potential.

A clone, then, isn’t all that different from any other character.